Jaipur (01/07 – 23.08) In the High Court of Rajasthan, in northern India, stands the only known statue of Manu, creator of the millennia-old Hindu social code that formalized the caste system, representing a symbol of inequality and oppression that many have been trying to overthrow for three decades, but without success.

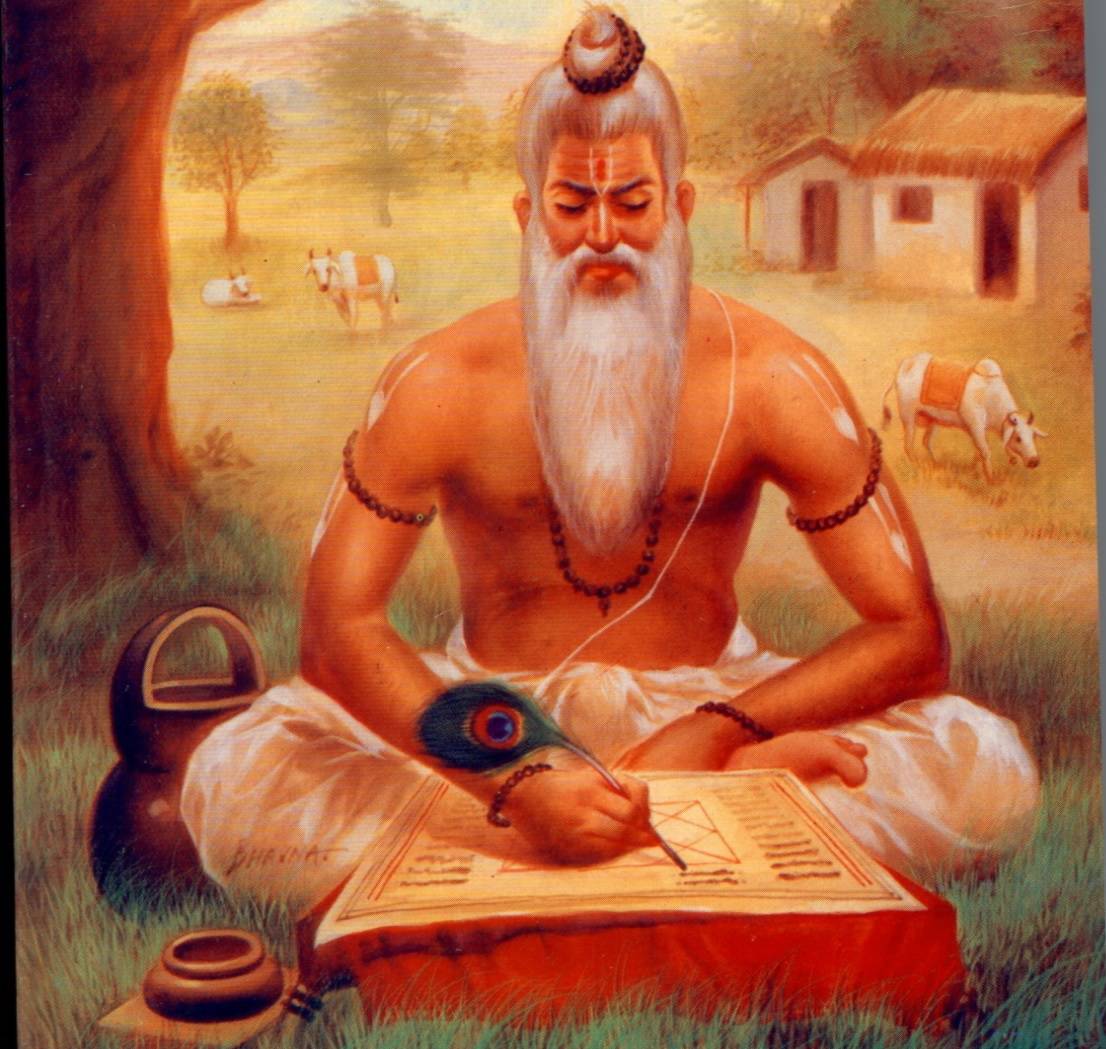

Since 1989, the statue occupies a privileged position in front of one of the buildings of the judicial complex in Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan state, and represents the mythological Hindu legislator Manu as a guru, with long beard and holding his work, “Manusmriti” (the Laws of Manu), in his left hand.

This book, dating back to the 2nd century BC, consists of 2,685 verses on the social obligations and duties of different castes and individuals, the correct way to govern or the punishments to impose on transgressors, among other aspects, but always benefiting the superior caste of the Brahmins or priests.

For centuries, the text succeeded in convincing outsiders that the Brahmins were truly superior, that status was more important than political or economic power, according to academic Wendy Doniger in the prologue to her translation of Manusmriti.

Even to this day, Manu remains the preeminent symbol – now a negative symbol – of the repressive caste system: It is Manu, more than any other text, that the untouchables burn in their protests, she explains.

The millennia-old Hindu caste system divides society into four major groups by birth, in order of purity: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaisyas (merchants) and Sudras (servants), which in turn are subdivided into hundreds of subcastes.

In the lowest strata of this system are the untouchables, or Dalits, considered impure, who perform degrading menial tasks, such as the manual collection of feces. According to the 2011 census, India has 166 million Dalits, constituting 16.2 percent of the population.

As per Manusmriti, the untouchables must live away from the villages, wear the clothes of the dead, eat in broken plates, receive payment in the form of leftover food, not be allowed to go out at night and must wear a recognizable symbol or badge.

Hindu society took these indications at face value for centuries, and many of them continue to be practiced at different places. It also laid ways of punishing them, synonymous with atrocities against Dalits.

If a man of a lower caste hurts a man of a higher caste with any part of his body, that same part of his body must be amputated, according to Manu’s code of laws, which prescribes punishments of a similar degree for things like even sitting at the same place as a higher caste man.

India had to wait until 1950 before it got its Constitution, three years after its independence from British rule, to officially ban the caste system, and promote positive discrimination in favor of the lowest castes.

However, the Constitution championed by the untouchable leader Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar has nevertheless failed to eradicate the marginalization.

“I have no example in the world of such exploitation and denial of rights for such a long period of time and with the intensity of untouchability,” Sukhadeo Thorat, director of the Indian Institute of Dalits Studies.

In this context, Dalit activists and other groups wonder how it is possible that the statue of Manu occupies a place at the premises of the High Court, a place where the values of the Constitution should be promoted first and foremost.

Permission to install Manu’s statue on the premises of Rajasthan’s High Court was obtained in March 1989 and attempts have been made since July of that year to withdraw it, always running into opposition from hundreds of lawyers and judges of the higher caste.

Since 2008, the responsibility of the legal battle against the statue passed to lawyer A.K. Jain, who admitted to EFE in his office in Jaipur that he has no “hope” of the case getting resolved in his favor, because “no one wants to touch the matter, so they keep it pending,” with few hearings.

After 1990, the next hearing was held in 2015 on the initiative of Jain, who witnessed “a court scene that resembled a battlefield,” with about 400 Brahmin lawyers coming together in a “show of strength,” while on the other side there were barely fifty.

Indian Supreme Court activist and lawyer Mehmood Pracha, during an interaction with EFE in New Delhi, recalled that Ambedkar had burned the “Manusmriti” in 1927, “and brought the Indian Constitution instead.”

However, he said right now it was not a good time to fight Manu’s followers because of the Hindu BJP government.