Climate-induced desertification is having adverse effects on the African continent each year the Earth continues to warm. It impacts the everyday lives of Africans – from their crops, livestock, and housing – to African wildlife and biodiversity. In this article, we take a look at the causes of deforestation in Africa, how this phenomenon affects the continent today and what is being done to curb its effects.

What Is Desertification?

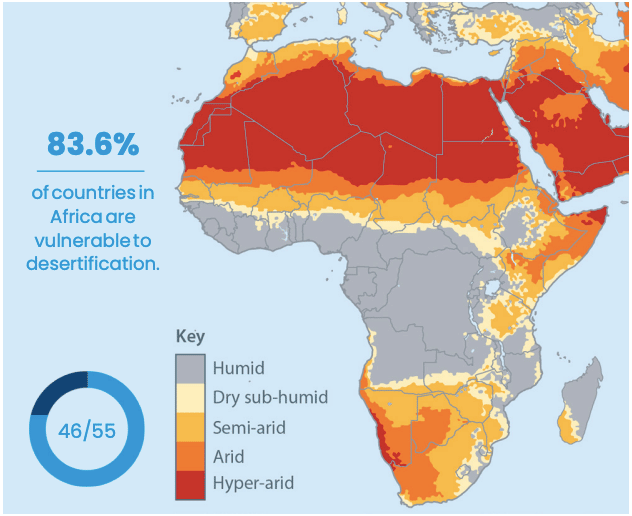

Desertification is “the process by which fertile land becomes desert, typically as a result of drought, deforestation or inappropriate agriculture.” It is where semi-arid lands, such as grasslands or shrublands, decrease and eventually disappear. According to the European Commission’s World Atlas of Desertification, more than 75% of the Earth’s land has already degraded. Unsurprisingly, the majority of desertification stems from climate change due to the destruction caused by extreme weather events, such as droughts and fires. According to the United Nations Development Program’s Drylands Population Assessment II, arid lands account for two-thirds of the African continent and three-quarters of Africa’s drylands used for agriculture.

The United Nations (UN) states that more than 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil disappear yearly due to desertification, which can happen for various reasons. The most common are deforestation, poor agricultural and livestock practices as well as the overexploitation of natural resources. Desertification has massive repercussions on the environment, including loss of biodiversity and vegetation, food insecurity, increased risk of zoonotic diseases (an infectious disease transmitted between species) such as COVID-19, loss of forest cover and shortages of drinking water due to the loss of aquifers.

A Brief History of Desertification in Africa

The origins of the word ‘desertification’ are most commonly attributed to French botanist André Aubréville’s 1949 work on African rainforests, though a study argues that it may even be traced back to the 19th-century French colonial North Africa. Talks of desertification in Africa began when the Comité d’Etudes commissioned a study to explore the prehistoric expansion of the Sahara Desert, which was obviously due to natural occurrences at the time. The phenomenon has existed in Africa for thousands of years and isn’t new. However, with societies developing and human activities rising, desertification has worsened considerably in recent decades.

Africa is home to one of the world’s most famous deserts, the Sahara, which is growing at a rate of 48 kilometres per year. Desertification and the expansion of deserts were not initially primarily due to human-induced climate change like they are nowadays. The world’s greatest deserts formed through natural processes interacting over many years, such as the evaporation of water, upwards winds, the descent of warm air and low humidity.

However, human activity has more recently come to either grow or shrink these deserts. To put human contributions into perspective, the Sahara has been growing rapidly since the 1920s – covering 10% more land than it used to according to a study by National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded scientists at the University of Maryland (UMD). The modern study of desertification that we are familiar with today, which considers climate change, emerged from studying the 1980s drought in the Sahel region – the most vulnerable region on the continent. The Sahel lies between the Saharan Desert and the Sudanian Savannah. It is a 3,000-mile stretch of land that includes ten counties and is under constant stress due to frequent droughts, soil erosion, and population growth which has increased logging, illegal farming and land clearing for housing.

The 1980s drought is not the first human-induced event that affected the Sahel region. The desert has historically experienced a long series of droughts, but one of the most significant is the Sahelian drought and famine of 1968. It lasted until 1985 and was directly linked to the death of approximately 100,000 people and disruption of millions of lives. Human exploitation of natural resources (such as overgrazing and deforestation) was originally believed to be the sole cause behind the drought. Still, it has been suggested that large-scale climate changes also triggered the drought.

Despite being the most affected area in Africa, the Sahel is not the only region dealing with desertification. Some of the most affected areas include the Karoo in South Africa, which has endured semi-arid conditions for the last 500 years, Somalia, which has suffered three major drought crises in the last decade alone, and Ethiopia, with 75% of its land affected by desertification and a major famine between 1983 and1985. With desertification becoming a more significant problem each year, these consequences will only increase if nothing is done to curb the climate crisis.

Desertification in Africa Today

As of 2022, it is estimated that 60% of the African population lives in arid, semi-arid, dry sub-humid and hyper-arid areas. The Sahel remains the most vulnerable and affected area in the African continent today, as well as globally. This makes it extremely difficult for people to work and make a living due to extremely dry land for growing crops.

“It’s been a rough year,” said Convoy of Hope’s Regional Disaster & Stabilization Specialist, Bryan Burr. “Drought after drought. Animals are dying. Crops aren’t growing. What food they do get is imported grain, and that’s not coming in now.”

Africa’s economy today relies on agriculture, with many Africans making high profits from harvesting and exporting crops such as cowpea, millet, maize, cocoa and cotton. However, it is estimated that as much as 65% of productive land in Africa is degraded – with desertification being the main culprit affecting 45% of the continent and the remaining 55% being at high risk of further degradation.

According to the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100), Africa loses 3 million hectares of its forests a year, leading to a 3% loss of GDP associated with soil and nutrient depletion. Due to the inevitable loss of land productivity, Africa has spent more than $43 billion on annual food imports, and farmers are losing out on profits due to soil infertility.

Image 1: Desertification and Climate Change in Africa

As a result of these consequences, it is smaller farmers and households that have suffered the most. Degradation of land and the depletion of healthy soils, tree cover and clean water means they can no longer grow crops and provide for themselves.

“There are almost no more trees, and the grass does not grow anymore. So, each year, we have to go further and further away to find grazing for our cattle,” a Senegalese cattle herder, Khalidou Badaram, told the BBC in 2015.

The consequences of desertification affect not only Africans but also the country’s rich biodiversity and habitats. The continent is home to the world’s second-largest rainforest, the Congo Basin, and hosts 17% of the world’s forests and 31% of woodlands across the Sahel and other regions. However, despite Africa’s abundant rainforests for wildlife to thrive in, desertification has crept in to disrupt some of what animals call home.

Dr Toroitich Victor, Response Officer for Africa, World Animal Protection, said that “in Africa, drought is one of the greatest disasters that threaten and cause animal deaths” as the changing climate is desertifying their habitat.

Since desertification has contributed significantly to farmers’ lack of fertile soil and land to grow and sell crops, many Africans have to turn to other means to make a living. Unfortunately, this may result in a decline of African animal populations. For instance, the Black Rhino is a native species to Africa but has been hunted into near extinction to meet the global demand for the Rhinoceros horn. These Rhinoceros horns can reach up to US$400,000 per kilogram.

Animals such as the African Elephant has suffered a similar fate due to the ivory trade. Gorilla numbers are also plummeting due to habitat loss. Farmers have been forced to make more room for agricultural development since much of the available land is no longer arable. Intensive agriculture methods are responsible for up to 80% of deforestation, the United Nation’s Global Land Outlook 2 report found, highlighting that desertification is having a knock-on impact on various environmental tragedies.

What Are We Doing to Stop African Desertification?

Desertification is becoming an increasingly important problem for much of Africa, so initiatives have been implemented to curb its spread.

“One of the best, most comprehensive solutions [to fixing desertification] is land restoration, which addresses many of the underlying factors of degraded water cycles and the loss of soil fertility,” the UNCCD Executive Secretary Ibrahim Thiaw told the United Nations.

With the Sahel region being the most vulnerable and heavily affected by desertification, an initiative known as ‘The Green Wall’ was put in place for the Sahara and Sahel in 2007. Its ambitious aim is to grow an 8,000-kilometre natural wonder across the entire width of Africa in order to increase the amount of arable land bordering the Sahara desert. The idea is that planting more trees will combat desertification, create jobs, increase food security and bring migrated populations back home to Africa.

The initiative is showing signs of significant progress. 18 million trees have been planted in Senegal since its launch in 200, and the growth of this figure will hopefully prevent the Sahara from advancing on the land most affected by desertification and reduce soil erosion in the process. 37 million acres of degraded land in Ethiopia have also been restored due to this initiative. The Great Green Wall’s goal for 2030 is to restore 247 million acres of destroyed land and create 10 million jobs in affected rural areas.

Due to the scale of disruption caused by climate change in Africa, The ‘Wall’ is only one of many initiatives in place. For instance, to recover lost rainforests and save the remaining forests left in Africa, the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) was launched in 2015 to restore 100 million hectares by 2030. The roadmap for development Agenda 2063 was also implemented to commit to several issues. These include ecosystem restoration, protecting, restoring and promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably managing forests and combating desertification. Lastly, a similar initiative to AFR100, the Pan-African Agenda on Ecosystem Restoration for building resilience, led to commitments to restore 200 million hectares of forest in Africa – a much more ambitious commitment than the AFR100 initiative.

Although it has taken over a decade to see significant improvements in reversing the devastating effects of desertification, the advances we have seen since initiatives were put in place are major. With millions of hectares of forest regained, which is only growing yearly, the outlook for restoring healthy green land looks positive. AFR100’s goal of restoring 100 million hectares by 2030 is not as far-fetched as we may think despite the ambitious goal, especially since the Great Green wall received $14 billion in funding for the next ten years at the recent One Planet Summit for Biodiversity. This financial support will vastly scale up efforts to restore degraded land, create green jobs, strengthen resilience and protect biodiversity. Despite the catastrophes caused by desertification, there is hope for a green future.

Source : Earth