Turkey may have finally let Finland into NATO, but it’s not budging — yet — on Sweden. And NATO just has to live with that.

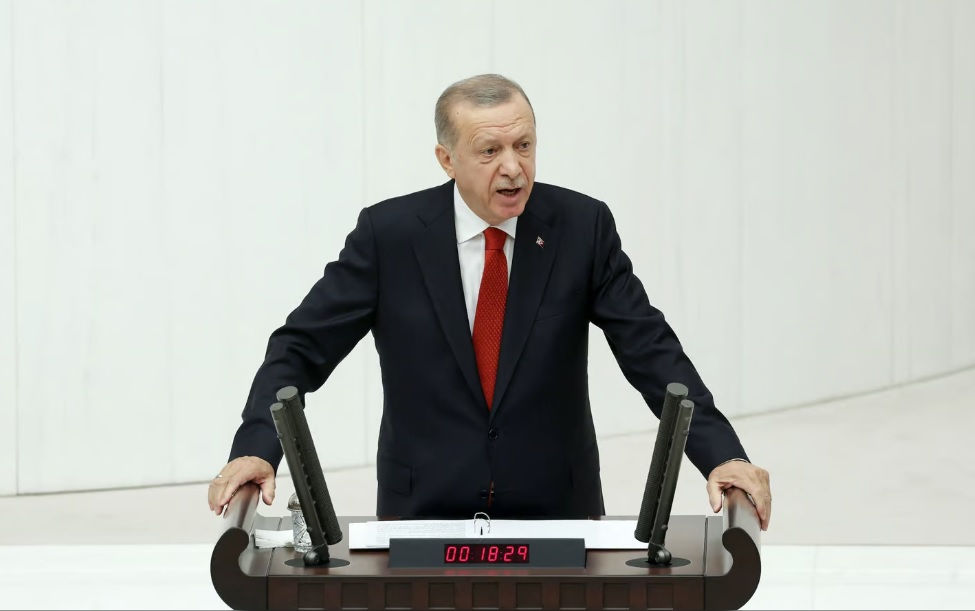

The unyielding blockade is the latest in a string of Turkish actions that have left the military alliance’s allies grumbling and eye rolling. In 2017, Turkey controversially decided to buy a Russian missile system. It has repeatedly attacked the very same Kurdish militia the U.S. had supported in Syria. And to this day, Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, still chats regularly with Vladimir Putin.

And, until late Thursday, Turkey had also blocked Finland from joining the alliance for months, even as war raged nearby.

Privately, some officials are bristling at Turkey’s obstructionist approach, its Russia-engaging foreign policies and democratic backsliding. In a symbolic move, the White House didn’t invite Turkish officials to its Summit for Democracy. And some observers are openly wondering how Turkey, a NATO member since 1952, even fits in the Western defense club.

Yet NATO officials and allies have evinced no desire to engage the issue. They insist NATO and Turkey are locked in a marriage of mutual convenience — and allies, as they’ve done for years, just have to figure out how to make it work.

Turkey, they note, brings the second-largest NATO army to the table. It actively contributes to alliance missions and operations — not a sure thing for all members. And critically, it sits on prime geopolitical real estate between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, controlling who passes through. Turkey’s Russian links could even make it a useful interlocutor in potential peace talks with Ukraine.

“Türkiye is an important NATO ally — and for many reasons,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg told POLITICO in an interview, ticking through a laundry list: geographic location, fighting the Islamic State, supporting Ukraine, keeping the world’s grain flowing.

“They’ve closed the Bosphorus Strait for naval ships,” he added, “which has reduced Russia’s capabilities to reinforce their presence in the Black Sea and around Crimea.”

NATO, in other words, needs Turkey, headaches and all. And it is willing to make compromises and play down disagreements to keep Turkey in the fold, illustrating the value the alliance is placing on harmony amid a destabilizing world. And Turkey, for its part, also wants to stay in the fold, even if it regularly goes rogue. It needs NATO’s protective assurances as the country eyes threats from countries such as Iran and even Russia.

“Turkey provides a security cushion to NATO,” said Sinan Ülgen, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe. “And definitely,” he said, “NATO provides a security umbrella to Turkey.”

A European diplomat was even blunter: “Of course Turkey needs NATO,” the diplomat said. But, the diplomat added, it is also “the elephant in the room.”

Ankara’s balancing act

Turkey’s foreign policy sets it apart from most NATO allies.

The country has condemned Russia’s invasion and provided aid to Ukraine, but is also refusing to sanction the industries fueling Moscow’s war. And since the war began, Erdoğan has met in person with Putin multiple times — in addition to their regular phone chats. He even accused the West of provoking Russia.

The country “has adopted an approach of balancing everything so pragmatically in order to maximize their own interests,” said another senior European diplomat, who, like other diplomats, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal alliance dynamics.

Turkish officials, however, see their country as a facilitator. In their view, Turkey is a NATO ally that can take on bridge-building roles Western capitals struggle to fill.

“Despite our strong disagreements on certain issues, we do have a functional communication channel with Russia,” said one Turkish official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Turkey, the official noted, helped broker the delicate deal between Russia and Ukraine to get landlocked piles of grain out through the Black Sea. The agreement “prevented a new food crisis,” the official stressed, adding that Turkey is also playing an active role in prisoner exchanges between Russia and Ukraine.

A second Turkish official insisted that “nobody can reasonably claim that we are an outlier in the alliance in any way” but said that “there are some allies that are insensitive to our vital and existential security concerns.”

Whether viewed as a disruptor or a facilitator, Turkey has been able to pull off its renegade role within NATO, a consensus-based organization, and even win concessions and influence.

In 2010, the alliance appointed a Turkish civil servant as assistant secretary general for defense policy and planning. NATO documents routinely underline the terror threat to the alliance — a nod to Ankara’s concerns.

Most other allies “wouldn’t want to be isolated, they wouldn’t want to be the bad guy,” said Jamie Shea, a former senior NATO official. Turkey, however, “doesn’t mind,” he added — it “gives Turkey enormous leverage and enormous power.”

The Sweden gambit

Ankara’s willingness to go it alone is now on full display as it holds up Sweden’s NATO bid.

Finland and Sweden applied for NATO membership together in May 2022. But Ankara raised concerns about the countries’ support for Kurdish groups and arms export restrictions.

In June, all three signed a deal committing Finland and Sweden to tighten their anti-terror laws, address Turkish extradition requests for terror suspects and clamp down on the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant group that has fought the Turkish authorities.

But as the months passed and NATO officials began insisting the two countries had met their end of the deal, Turkey didn’t budge — arguing the progress was insufficient.

Experts say the delay is in part linked to domestic politics — Turkey will hold elections in May and tensions with Stockholm escalated after a Quran burning at a protest earlier this year. Turkey is also, they added, likely trying to squeeze the United States on issues like the blocked export of F-16 jets.

Earlier this month, Erdoğan finally said his country would move ahead with Finland’s ratification — while leaving Sweden behind, at least for now.

“The Turkish idea of splitting the membership, and approving Finland was very smart,” said Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution who specializes in Turkish domestic and foreign policy. “I think it’s helped Turkey immensely to make a case that their opposition to Sweden isn’t done at Russia’s request, but it is to do with Turkey’s own interests and demands.”

There is widespread speculation within NATO that the Turkish parliament could sign off on Sweden’s bid after the country’s election. Ankara, Western officials and experts say, has no interest in dragging its feet forever. And Hungary — which has similarly yet to approve Swedish membership — is unlikely to block accession on its own.

In public, NATO officials had stressed for months that Turkey has legitimate concerns but that Sweden and Finland have done their part and deserve approval. In private, however, some officials have expressed annoyance — and not just at the Turkish leadership.

Stoltenberg’s “appeasement policy towards Erdoğan has failed,” said the first European diplomat.

But the NATO chief insists the alliance must take Turkish concerns seriously — and that he still hopes Sweden could become a member after Turkey’s planned May elections and before the alliance’s annual summit on July 11.

Turkish officials, meanwhile, say that their record shows they support NATO enlargement. “The moment we see Sweden fulfilling their commitments,” said the first Turkish official, “we will start the ratification process as we did with Finland.”

And there is a sense that despite qualms about Ankara’s behavior, its maverick foreign policy could come in handy down the road.

Peace talks in Ukraine are “not on the cards at the moment,” said Shea, the former senior NATO official. “But you know, when they come back, who’s gonna play the mediator? Is it going to be China or Turkey? I put my money on Turkey.”

Source : Politico